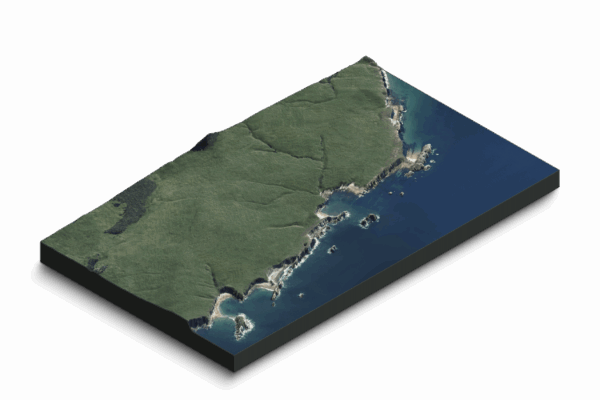

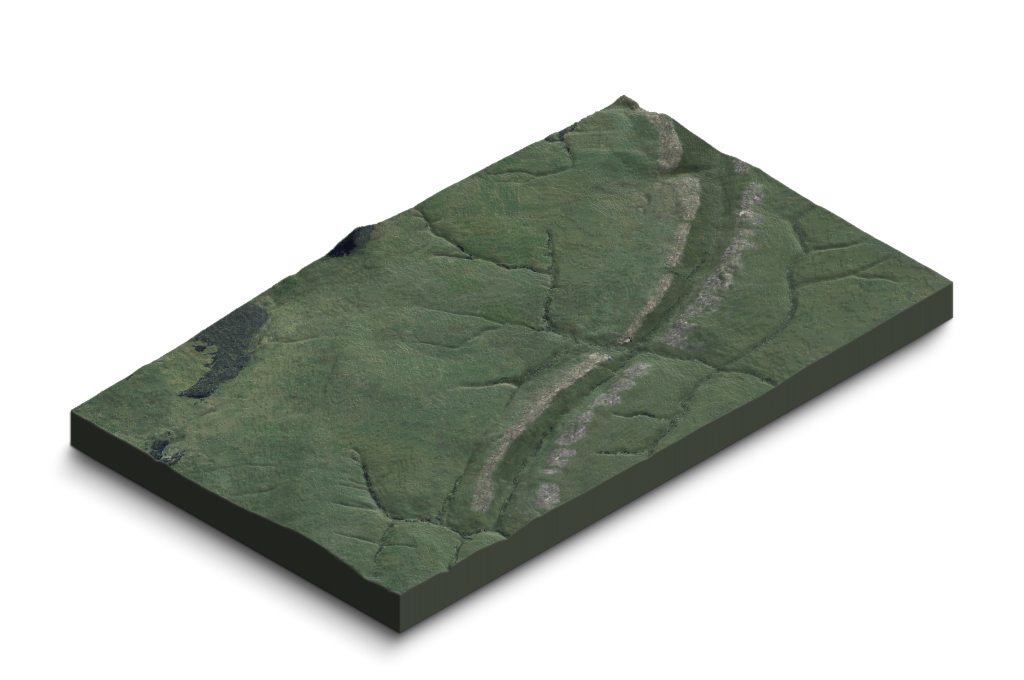

Costa Quebrada is a privileged setting for enjoying and understanding the geological processes that shape the landscape. The geopark is characterised by a major structural feature: a large fold known as the San Román–Santillana Syncline, which extends across the entire territory from northeast to southwest. This structure clearly reveals the magnitude of the forces acting within the Earth, with rock strata at its northern and southern ends locally tilted to near-vertical positions.

These rock layers contain invaluable information, allowing us to reconstruct a geological history spanning more than 100 million years. They vividly illustrate the ancient environments in which the rocks were deposited, as well as the folding and uplift processes resulting from tectonic plate movements.

Intense marine erosion, combined with the complementary action of rainfall and surface and underground water circulation—through rivers, streams and subterranean flows—has created a unique geological landscape. Along the cliffs and wave-cut platforms carved by the sea, the geological substrate is laid bare, revealing the inner structure of this exceptional territory.

A Folded Structure

–

The geopark is defined by a folded structure: the San Román–Santillana Syncline. Here, a complete record of materials accumulated since the Lower Cretaceous is preserved.

Marine Erosion

–

Wave action along the Costa Quebrada coastline exposes outcrops of outstanding stratigraphic value on cliffs and abrasion platforms. These features, shaped by differential erosion, create the distinctive landscape of the geopark.

The Evolution of the Landscape

–

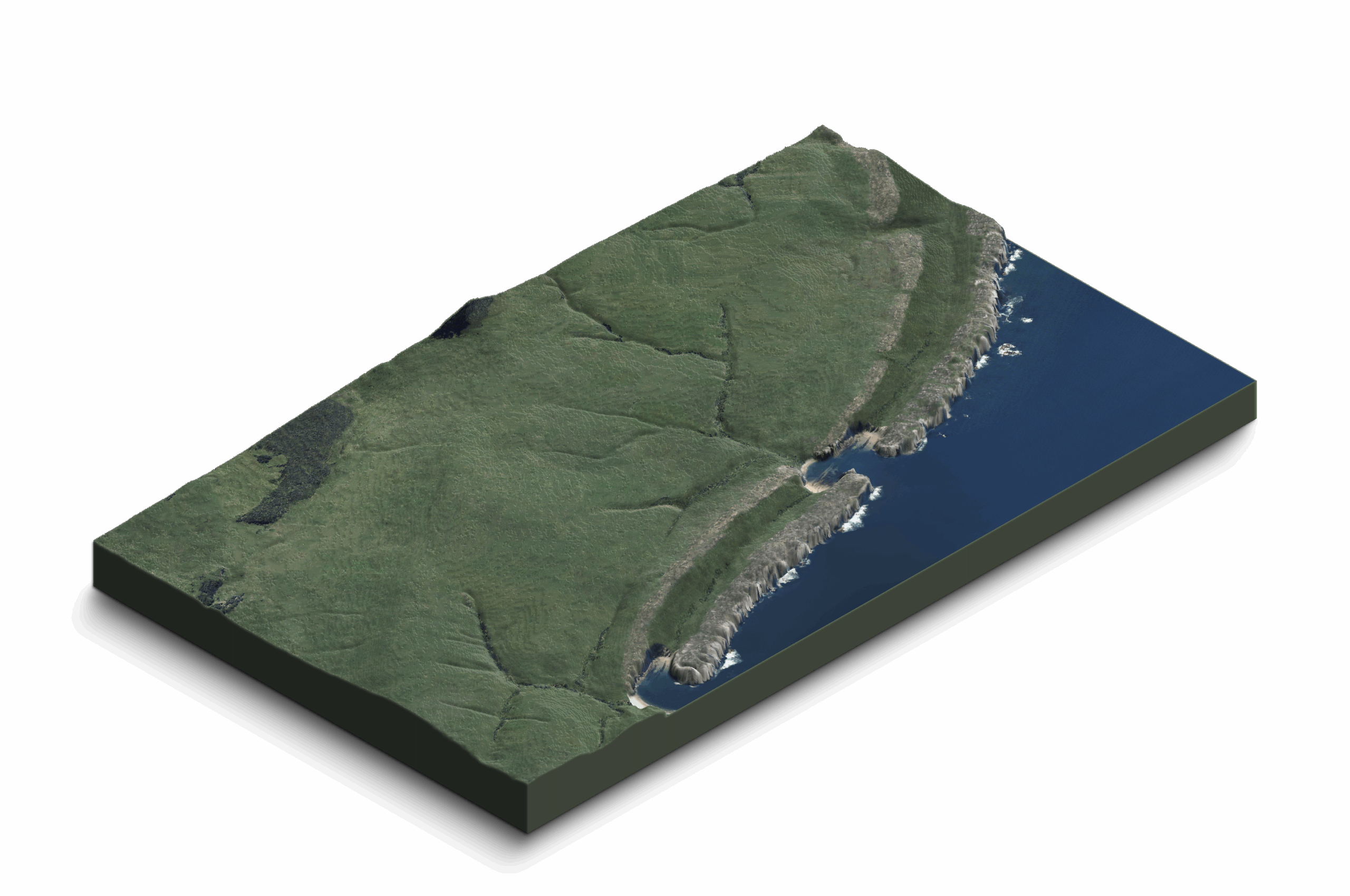

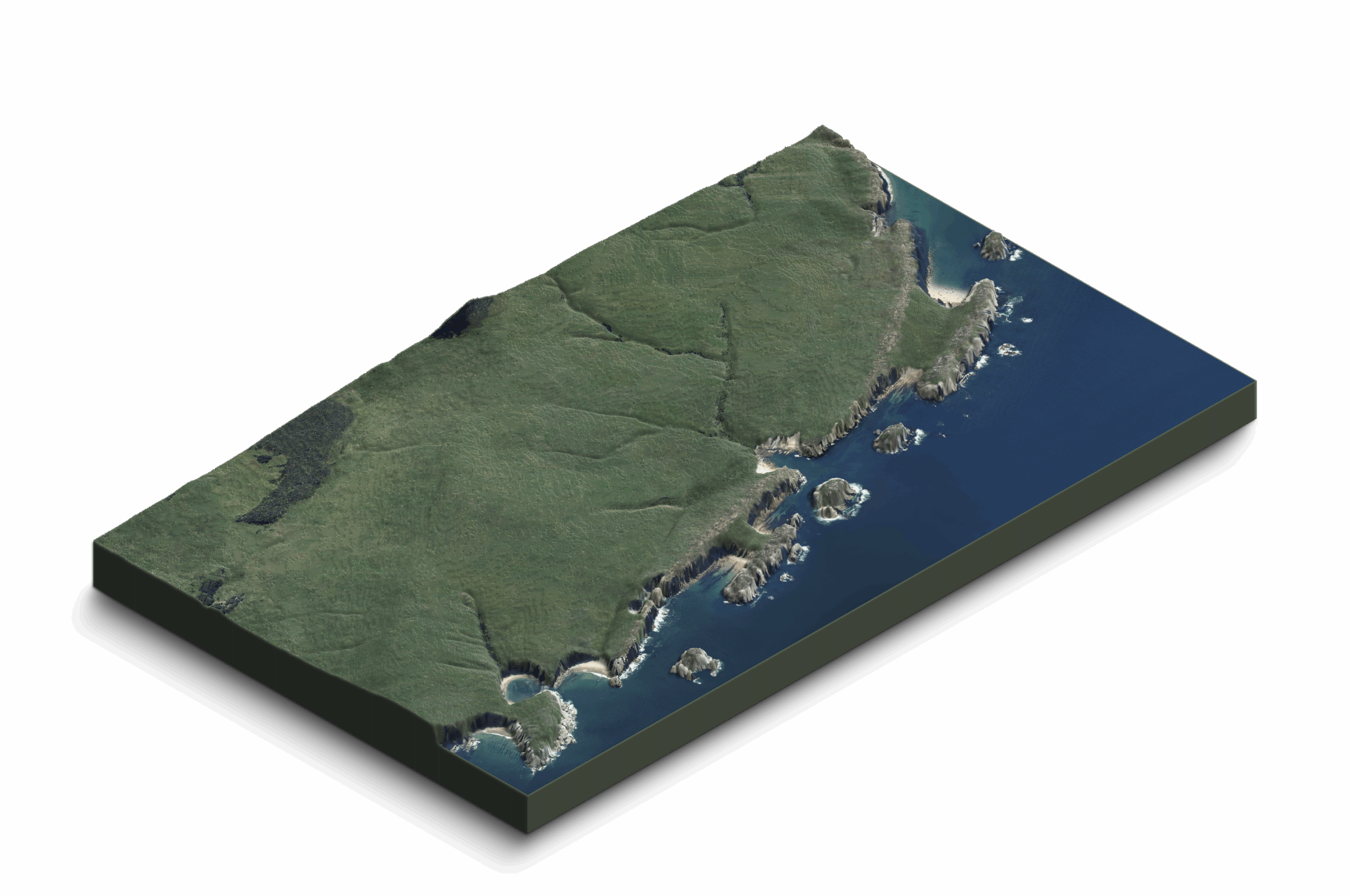

Costa Quebrada not only displays, along a short stretch, an extraordinarily rich and attractive array of coastal landforms but also clearly demonstrates the processes shaping the coastline, allowing us to reconstruct its evolution over time.

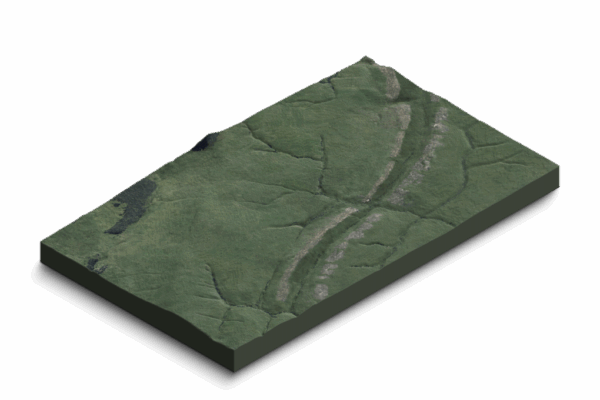

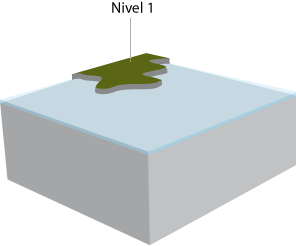

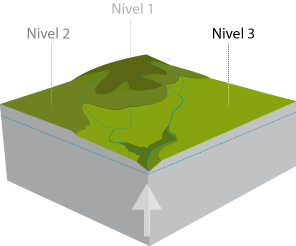

1

During a glaciation, sea level retreated several kilometres, exposing a vast plain shaped by river systems.

Two long limestone ridges cross the landscape, forming barriers that rivers could only breach through fractures and faults.

This was likely the dominant landscape when the inhabitants of Altamira crossed these coastal plains to reach the shoreline—about 5 km seaward of the present coast—to fish.

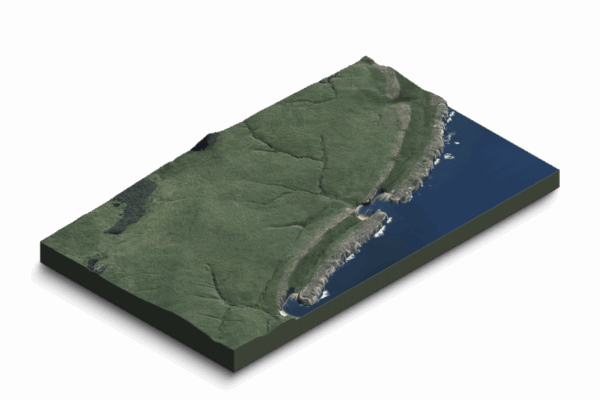

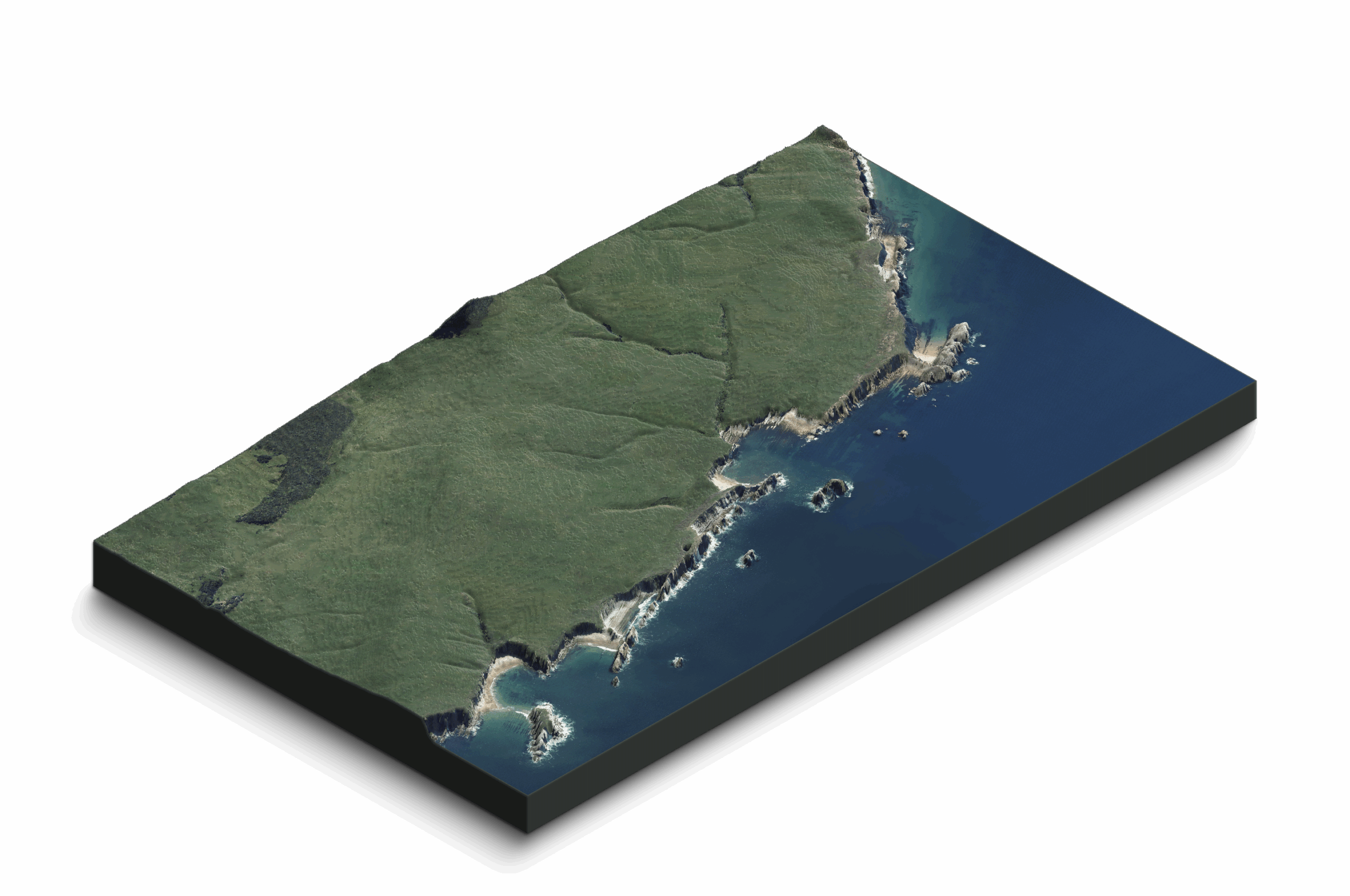

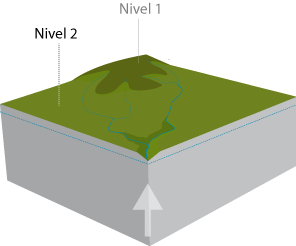

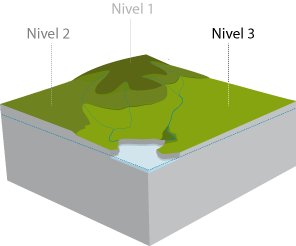

2

Following the glaciation, rising sea levels flooded the plain.

Wave action destroyed weaker rocks and advanced until it encountered the highly resistant limestone ridges.

Erosion was temporarily halted until the sea penetrated through fractures and rapidly eroded softer materials, forming small coves that gradually widened.

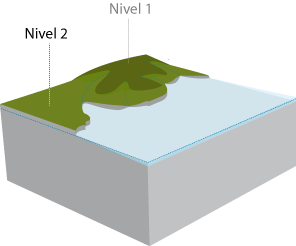

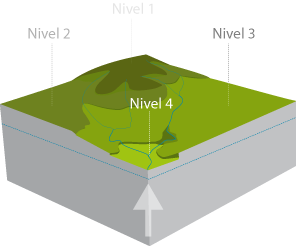

3

Some remnants of the more erodible rocks were preserved where they were protected by the limestone ridge, which itself was slowly dismantled.

Wave erosion was again slowed by a second limestone ridge, but as it passed through openings, it began to erode the softer marls behind.

Where marine erosion gained access, curved coves were carved, within which beaches developed.

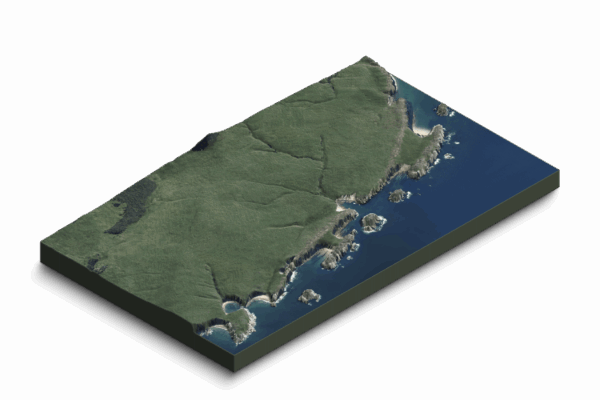

4

Continued erosion reduced the limestone of the first ridge to small aligned coastal islets, locally known as urros.

The coves, bordered by high cliffs, continued to widen, encroaching upon the gentle landscape of hills and river valleys.

And erosion continues its advance…

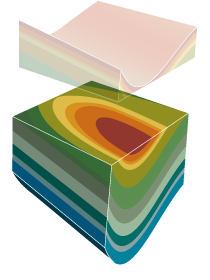

Three-Phase Formation

–

The dominant structure of the geopark originated through three phases, forming a complete geological cycle. The sediments that now form the rocks of the geopark were derived from the erosion of older materials, just as sediments produced by current erosion will eventually become the rocks of the future.

1

Sedimentation

2

Folding

3

Erosion

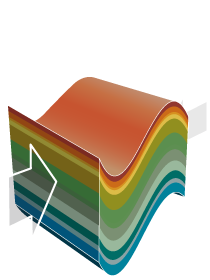

Marine Terraces

–

Relative fluctuations in sea level are responsible for the erosional processes that shape this landscape. As materials are folded and uplifted, successive sea levels generate several distinct marine terrace levels.

1

Marine erosion of an abrasion platform

2

Uplift of the land and/or rise in sea level

3

Marine erosion of a new platform

4

Further uplift and/or sea-level rise

5

Marine erosion of a third abrasion platform

6

Further uplift and/or sea-level rise

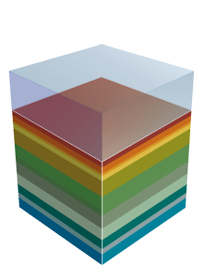

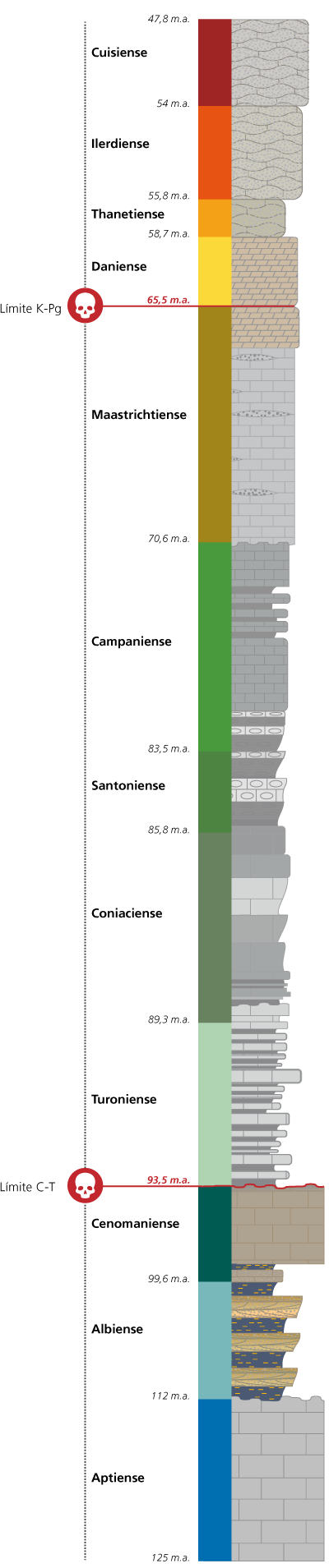

Stratigraphic Column

–

This diagram represents the rocks that outcrop in Costa Quebrada, indicating their ages in millions of years (Ma) and their lithological nature. Two major temporal boundaries are also shown: the Cenomanian–Turonian (C–T) and the Cretaceous–Palaeogene (K–Pg, formerly K–T) boundaries, both associated with biological extinction events.

The Rocks of the Geopark

–

The long geological history of Costa Quebrada, together with the succession of events that took place here, resulted in a diverse array of sedimentary rocks grouped into clearly differentiated formations.

Each formation represents a chapter in the vast geological book that tells the story of our planet. From these chapters we extract the information that allows us to complete that narrative.

The different rock types present in the geopark are listed below in increasing order of age.

1

Deposits younger than 2.6 million years

SANDS

CALCAREOUS TUFA

In addition to Pleistocene fluvial terraces and raised beaches (excluded from the map for clarity), Holocene beaches and dunes, decalcification basins, estuarine deposits, and alluvium are present. Biogenic tufa forms at points where carbonate-rich freshwater from streams and springs meets marine waters.

2

Peña Saría Formation (54 Ma)

CALCARENITE with Schizaster sp

MARLS AND CALCARENITES

The youngest consolidated materials in Costa Quebrada, approximately 150 m thick, composed of calcarenites with interbedded marly layers. Rich fossil fauna including echinoids and sponges.

3

Estrada Formation (55.8 Ma)

NUMMULITIC LIMESTONE

CALCARENITE WITH CHERT

About 100 m thick, formed by calcarenites and sandy limestones, with levels of nummulitic limestone and chert nodules derived from sponge fossils.

4

Sancibrián Formation (58.7 Ma)

THANETIAN LIMESTONE

Approximately 20 m thick, consisting of compact limestones with algal fossils, highly soluble and frequently karstified, with glauconite-rich marly interbeds.

5

San Juan Formation (65.5 Ma)

THANETIAN LIMESTONE

About 70 m thick, the first Paleogene materials, composed of sandy and microcrystalline dolostones and biopelmicritic calcarenites.

6

Cabo de Lata Formation (70.6 Ma)

THANETIAN LIMESTONE

Up to 160 m thick, representing the final Mesozoic deposits, with limestone levels increasingly rich in sands, including sandstone lenses and conglomerates.

7

Sardinero Formation (Upper) – 83.5 Ma

NODULAR LIMESTONES

Around 200 m thick, formed by siliciclastic calciturbidites overlain by marl-limestone rhythmites and nodular limestones generated by Thalassinoides-producing organisms.

8

Sardinero Formation (Lower) – 93.5 Ma

MARL–LIMESTONE RHYTHMITES

MARLS WITH UNCONFORMITIES

TURBIDITES

Approximately 400 m thick, composed of glauconite-rich clayey marls and calciturbidites, locally containing fossil assemblages dominated by echinoids and ammonoids.

9

Altamira Formation (99.6 Ma)

LIMESTONE

About 120 m thick, consisting mainly of sandy limestones, with a clearly calcareous upper member and a lower member of bedded limestones interbedded with marls, capped by a notable hardground.

10

Suances Formation (112 Ma)

CROSS-BEDDED SANDSTONE

SILTSTONE

Roughly 100 m thick, formed by progradational coastal detrital facies cycles, alternating carbonaceous siltstones with sulphur indicators and cross-bedded sandstones.

11

Reocín Formation (125 Ma)

URGONIAN LIMESTONE

Up to 200 m thick, composed of reefal micritic limestones with rudists, showing secondary dolomitisation and lead–zinc mineralisation. Rudists and corals are commonly observed.

Geological History

–

When the earliest Cretaceous materials of Costa Quebrada began to be deposited around 120 million years ago, they accumulated in the warm, clear waters of the Tethys Sea. On distant landmasses, reptiles dominated life on Earth, while extensive reefs formed below the surface, built by rudist molluscs and corals.

These reefs generated massive Aptian limestone bodies that today, once uplifted, form prominent rocky outcrops along La Marina and in the limestone massifs east of the River Miera. Their mining importance in Cantabria has been historically significant, as evidenced by sites such as Cabárceno, Reocín, Puerto Calderón and the many quarries of Camargo and eastern Cantabria.

But in the long history of our planet, nothing lasts forever. After around five million years, the tranquillity of these waters was disrupted by changes in precipitation patterns and sea level.

During the Albian, around 112 million years ago, sediments carried by rivers from the south and west buried the rudists and corals, preventing their survival here. Initially, only finer sediments—silts and clays—arrived, loaded with plant debris, wood from forests, and small fragments of resin. In some of these resin fragments, amber, ancient insects have been trapped elsewhere in the basin.

The dark silts, as they accumulated, filled the basin and advanced the coastline. Near the shore, sandbanks from a vast beach buried the silts. However, sea level rose several times, and with each rise, the dark silts buried the sands again, forming thick layers until the basin was filled and the sands returned.

In this way, the siltstones and sandstones found today in the Somocueva isthmus were formed, and they can be found along the entire central coast of Cantabria, from Suances to Comillas and the lower Nansa valley.

These cycles of silts and sands were not exactly the same. Over time, each new layer of sand contained more calcium, so that gradually the sand deposits transformed into limestone layers, in which the numerous dying marine organisms became trapped and fossilized. Ammonites, sea urchins, snails, corals, sponges, and many other organisms formed rich marine communities.

This limestone gradually sank in the basin until deposition ceased. At the end of this process, a significant decrease in dissolved oxygen in the sea occurred, causing a major mass extinction of marine species.

Thus, a layer of ochre-coloured calcarenites was formed—the same Cenomanian calcarenites universally recognised as the rock in which our ancestors painted their beliefs and worldview at Altamira.

The inert reef, sunk into the depths of a colder, less lively sea, was then buried by new sediments. Clays, almost devoid of life, appeared.

As these sediments were deposited, the climate was not constant. Warm and humid periods of tens or hundreds of thousands of years alternated with long cold and dry periods. These oscillations were reflected in the type of sediments arriving at the basin.

For long periods, abundant rainfall carried clay into the basin, while at other times, clays were less abundant and shells and calcium-rich remains dominated. This calcium cemented the clays when abundant, forming interbedded harder layers. In this environment lived irregular sea urchins, corals, sponges, ammonites, bryozoans, and many other organisms.

This cyclical process was repeated countless times from the Turonian to the Santonian, giving rise to the successive narrow layers of marl and gray limestone that can be seen along the cliffs of eastern Costa Quebrada.

From the Maastrichtian, around 70 million years ago, this small basin began to rise slowly, allowing sands to progressively reappear, together with the influence of marine currents. In this environment, sandy limestones were deposited between Covachos and San Juan de La Canal.

This continued until the end of the Mesozoic, 65 million years ago. With the mass extinction that ended the reign of the large reptiles, many other species also disappeared. At this time, the sandy materials were exposed to the elements, in coastal brackish lagoons. Here, very soluble rocks—the dolomites of the La Canal cove—were deposited.

The coastal environment of these sandy deposits, strongly reworked by currents and waves, produced the most recent materials of Costa Quebrada: the calcarenites and limestones in the vicinity of Virgen del Mar. In this agitated environment, numerous sea urchins, annelids, and sponges lived.

At this time, the collision of Africa with the European continent began, compressing the Iberian Peninsula against Europe and uplifting all the southern European mountain ranges: the Cantabrian Mountains, the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Balkans, and the Carpathians.</>